After exchanging a lot of conversation and ideas with Charlie Judkins within the past week or so, he and I have been trying to figure out more pianist names as far as these records go, of which not much luck has been had by us in this matter. Two names were found, but they were supposedly Victor pianists, which is just what we need to hear, since there was already a glut of pianists there in 1900 to 1905. These two names were actually those of two women, unknown ladies that have no significance in Rag-Time communities and publications, which is unfortunate. These ladies are not well or highly praised, despite their mentioning specifically under a Victor section in a New York Newspaper. Nothing detailing these ladies has been found thus far after just seeing their names. Other than that, we haven't come across a treasure trove of pianist names yet. That will hopefully come later, in wherever one of us happens to find it. Victor and Zon-O-phone will remain the hardest to tell as far as pianists go with early disc records. With that, Lambert will stand as the hardest to tell with cylinders.

Even with all this confusion, I think I have come to a realization. I was listening to a take of "The Nigger Fever" by Frank Mazziotta, which has some of the strangest rhythmic patterns I've ever heard on an early piano accompaniment record. With all of this strange left hand playing, I listened to two early Arthur Collins Edison cylinders just afterward, these two in fact:

We have known for a while that Frank P. Banta is on both of these cylinders, with all of the evidence present on many later Victors from 1901 to 1903, and my previous explanations about this. After several listens to these records back to back, I realised that the pianist making up those strange yet very syncopated left hand things was Banta! The pianist identification on this record seemed irritatingly hard, until I inadvertently listened to the records to create the solution comparison for the issue. I cannot share the link to this Zon-O-Phone of "The Nigger Fever", in order to respect the one who shared it with me, but I will describe what is heard and why it sounds similar to the two brown waxes linked above. The strange rhythm patterns are heard primarily on the first one, "Zizzy Ze Zum Zum" in this case, which immediately caught my ears, as it wasn't identical rhythmically, but the similarities and touch to it were suspiciously present. These were all slight and strange characteristics of...

Frank P. Banta!

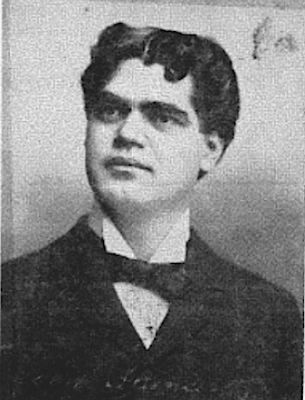

(this is a sketch I did of him recently, really trying to perfect his strangely structured profile, I'm still trying to get it right...)

His attributes all check in on "Zizzy Ze Zum Zum", from that strange rhythmic pattern, that can be heard mostly at the solo sections and also at the choruses, to the fifths that Banta was known for playing on Victors. The final chord on that record involves a big and loud fifth, which really sounds like all of those early Victors, and on this 1899 cylinder with an unspecified label(this cylinder is still up for guesses on the pianist). It is still a strange and idiosyncratic thing that Banta played fifths n his left hand, since he was not a mid-western pianist nor native, which is usually where that originates from(from states such as Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri). The second cylinder listed "All I wants is my Chickens", has all of the fifths that is on the Zono of "The Nigger Fever", and even some of that strange rhythmic thing, which can be heard in the Choruses and very well at around 1:22 to 1:25. That very rhythm is exactly the same as the strange thing on the Zono of "The Nigger Fever", just played a little differently, and better yet, earlier on in the history of Rag-Time.

What does all of this lead to? Well, it confirms that an Edison and Victor pianist played for Zon-O-phone in 1900-1902. This gives a little more insight into the queer and well-hidden studio of Zon-O-phone, but that still doesn't explain the brief period after that where Hylands worked there, but that's a different story that I have already addressed in previous posts. As always, I am not entirely sure if this pianist that I mean here is Frank Banta or Fred Bachmann, as it's one of the two. Remember that Bachmann was the only other studio pianist at Edison who moved to Victor after 1900. In this case however, it seems more likely to be Banta, since the two Collins cylinders were recorded so early on(1898), and Banta was known already to have been a Rag-Time studio pianist(so was Hylands as we know), and had several years of pre-ragtime on Hylands by performing with Vess Ossman. That don't mean anything when talking about Hylands' Rag-Time status however. In many ways, Hylands had the best amount of luck and status in the early(white)Rag-Time community.

Since I took a few listens to "All I Wants is my Chickens" while writing this, I realised that the ending solo on it is almost identical in phrasing and feel as the Denny cylinder of "The Change Will Do you Good" on an unconfirmed label. Really take a listen! They are freakishly similar.

We are still to yet find more names associated with Zon-O-phone, since it seems now that they had a flaming pan full of hot pianists, which included Banta and Hylands.

With all of this said, it makes these two wild Zono's up for some more educated guesses and listening:

(these were recorded on the same day, so whoever it is, it's the same pianist on both of them, one guess leads to two in this case, which helps a whole lot.)

Another matter I would like delve into is the time that Fred Hylands was actually hired to work at Columbia. it remains very hard to tell and pick out a timeframe that Columbia hired Hylands, even though the date range is early 1897 to early 1898. It can't be late-1896 since he was not really in New York until around that time, and it can't be later than early 1898 because he's mentioned in early 1898 issues of The Phonoscope, and the piano accompaniment had a polar shift in style in late-1897 at Columbia. After discussing the matter over with Charlie, we really think that he was hired by Columbia in earlier 1897, more like March of that year or so, earlier than we could have assumed, since he was reportedly working as a music director and stage accompanist at Pastor's Theater, and others as well. Since that was the case, he must have been in the studio by day, and by night was working in the pit and herding theatrical cats. The two records that have us suspicious of him working there early on are these two puzzling records:

Billy Golden's "Uncle Jefferson" from earlier 1897

and "The Jealous Blackbird" from around the same time in 1897

The Billy Golden record listed above is still notoriously hard to identify the pianist on, until Charlie and I sorted it through, picking out small sections and comparing them to other records we heard with Hylands from several years later. The recording of "Uncle Jefferson" particularly has many of the more idiosyncratic aspects of Hylands' style, which include the very "dotted" syncopated patterns and the heaps of tenths and twelfths. The one thing that really got us suspicious is the final rolled chord and tenth, which is something that was distinct to Hylands on Columbia records. If you're listening close enough to "The Jealous Blackbird", you'll notice that there's some of that rolled chord and tenth thing there too, which is very weird, but somehow they stick out. A record that comes to mind that has this tenth with a fifth and a chord ending is a strange 1899 cylinder by Len Spencer and Hylands of "My Josephine"(of which I can't share with you, sorry...). Spencer does a whistling chorus after the first verse, and after the whistling chorus, Hylands plays a short solo, where just at the end of it, he hits exactly the same thing as he does at several parts of "The Jealous Blackbird" with the fifth thing and ends on exactly the same chord on both records. It's starting to pull itself together it seems, as the similarities are beginning to make more sense, and are untangling just a little. It seems that the pianist on the 1897 records of "The Jealous Blackbird" is the same as Len Spencer's 1899 recording of "My Josephine", which tells you a lot, and that that pianist had been there for a while by 1899. Much or how the pianist plays behind Spencer on "My Josephine" is actually similar to how Hylands' "You Don't Stop the World from Goin Round", was formally written believe it or not, so that really throws up a frantic red flag about the pianist here.

The motion stands that Hylands worked at Columbia in earlier 1897, until we find something that contradicts all aspects of the statement.

Hope you enjoyed this! Sorry about posting for so may days, school has been taxing and time-consuming this week, and hopefully I'll get to post more frequently this next week.