The name Fred Hylands is mentioned very often on this blog, as he was not only a prominent studio pianist at the prime of the early Rag-Time era, but was also an important part of the comedic side of early Broadway. His name and influence fits into many subjects that go into this line of study. One of these subjects is the title of this post. The under-the-table dealing of music in the 1890's is a very understudied topic, as it simply wasn't written about often. One of these strategies that we have all heard of is handing a singer or performer an advance copy before the music is published, and surprisingly, this happened more than most people think. There weren't specific publishing firms that were begun by recording stars to unite the two parts of the music business, early on in the 1890's that is.

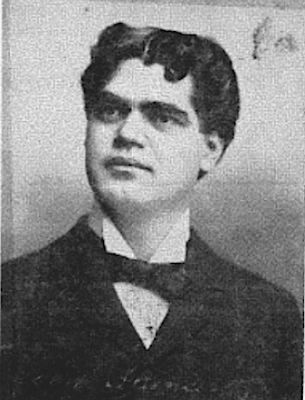

One famous composer-phonograph singer friendship was

Monroe Rosenfeld and

Len Spencer.

Most people don't know about this friendship, since it was well-hidden, but advertised occasionally in earlier editions of The Phonoscope. We know of many composers that Spencer endorsed early on, but one of the first would logically be Rosenfeld and also Barney Fagan. Rosenfeld came first, since his early "negro dances" were so popular, he also wrote lyrics to these pre-ragtime pieces, many of which Spencer became well-known for recording. Many of Rosenfeld's pieces from the 1880's were minstrel songs with slightly syncopated melodies, and with that, Spencer was bound to make hundreds of rounds of any of them. When speaking of this, I mean early on in Spencer's recording days, in the era where he worked regularly with Issler's Orchestra, 1892 to 1896 that is. The solos he made during this time were done under pseudonyms for the most part, but he was still known as the prime coon song singer on phonograph records. With this fame, the composers and publishers took an interest in Spencer, and kept their ears open for a time to hand him an advance copy of a new song. This probably happened with Spencer a few times in the mid-1890's, though it's not well-documented, according to others in the business, it did happen with Dan Quinn and J. W. Myers. Quinn stated in some of his letters to Jim Walsh that publishers handed him songs before they were published to singer before all the others got to it,he claimed to be the first one to sing

This great early Rag song with a very racist cover(typical for 1896...).

I'm not sure whether to believe that Quinn was handed an advance copy of this in 1896, but it's not impossible. I would believe it more if he said that Spencer was the one who got it first. I have seen so many advertisements that mention Spencer's record of "The Bully" as being one of his best records, and the most popular as far as his individual records go. This had to be so, since it was reported that Spencer was making rounds of this tune into early 1898. I don't know who was handed the advance copy first, even if Quinn stated that he was the one who got it first, not everything he said is to be trusted, remember. Other than Quinn's "Bully Song" statement, there wasn't much early music dealing in the era before 1897, though there was probably more than what we are presented in this matter.

It took until the "rag" fad to spread in 1896 for music publishers and composers to take more of a direct interest in recording stars. New publishers such as Joseph Stern took in some of the most popular studio stars under Russell Hunting's obliging with the Universal Phonograph Company. Many of their advertisements are in editions of The Phonoscope, here is their earliest one:

This came from the January 1897 issue of The Phonoscope.

Their ads were often in pieces of music published by Jos. Stern in 1897, of which I have one of these buried in my sheet music collection. They were usually small triangle-shaped things that said simply that the song this is on can be found on records made by the Universal Phonograph Company. That's perfect in illustrating this point of publisher and recording artist, so early on in the era as well. 1897 would be toward the beginning of this idea of uniting the two aspects of the music business, as most people think of this happening in the 1910's and 1920's, but in reality, it began in the late-1890's. The Universal Phonograph Company didn't last to see the end of 1897, but it proved that a publisher could join with a record company to sell music and make records. This quick venture for the Columbia staff got everyone thinking about beginning something else like that, but they needed a better publisher for the job.

Composers still remained friends of many studio stars, such as Barney Fagan and Len Spencer or Quinn and May Irwin. It took until Columbia threw out their old pianist in mid-1897 for this idea to resurface. Fred Hylands was not yet a publisher as we know, but the ideas were formulating. There weren't any reports of music being dealt under-the-table in 1897 and 1898 at Columbia and Edison, but by early late-1898 and early 1899, the staff had begged Hylands enough to begin a publishing firm, and so he did. He was exactly the kind of publisher that Columbia's staff wanted and needed, since he worked there, it all seemed to work perfectly.

No one saw their finish of course.

But that doesn't matter just yet, it was the perfect everything for Columbia. If you really want to talk about some severe under-the-table music dealing, Hylands Spencer and Yeager is the firm to study.

Pretty much everything that Hylands published was given to someone as an advance copy before he published it. This was especially so with anything he wrote(durr...). The instrumental music was given out after publication, but not the vocal pieces. Hylands handed his "You Don't Stop the World from Goin Round" to Len Spencer before he published it, so they could record it first, then sell the music, and he also did this with his "Prize Cake-Walker is Old Uncle Sam", and he gave that one to Dan Quinn of all people(that's kind of strange if you think about it). The ladies that Fred took a liking to eventually were ones who got music before it was published, such as Ada Jones, Sallie Stembler, and some of his wife's friends in the performing business. As the firm began to fade by early 1900, Hylands stopped handing out advance copies, as someone might have told him to end his habit of doing that, or something else, I really don't know, but it seemed that he stopped doing that after the end of 1899. It was around this time that everyone involved saw their finish, or Fred's in this case since he was the one who was going to take the harshest blow after it fell through. After the firm's end in November 1900, the idea of publisher and recording star lost its novelty, and all the old Columbia stars didn't bother to associate themselves with specific publishers or composers any more after that.

The second wave of studio stars adopted some of these ways, as many collectors are aware of the Collins and Harlan friendship with Theodore Morse, which lasted over a decade. Harlan had been part of Hylands' publishing firm, but after about five more years, Harlan was working not only with Collins, but found Theodore Morse a better asset than Hylands, which is many ways was a smart move on Collins and Harlan's part. This 1890's tradition carried on into the 1910's, 20's and even the 1930's in fact, and it seemed to become a much less hidden subject as the decades went on, making it not as sleazy and interesting as it was early on.

*I just want to take a moment to send my love and regards to Tom Brier and his family, as he was recently in an awful car accident and will take many months to recover. We will miss you at Sutter Creek this weekend! Some of the soul of the festival is lost without Brier there.*

One famous composer-phonograph singer friendship was

Monroe Rosenfeld and

Len Spencer.

Most people don't know about this friendship, since it was well-hidden, but advertised occasionally in earlier editions of The Phonoscope. We know of many composers that Spencer endorsed early on, but one of the first would logically be Rosenfeld and also Barney Fagan. Rosenfeld came first, since his early "negro dances" were so popular, he also wrote lyrics to these pre-ragtime pieces, many of which Spencer became well-known for recording. Many of Rosenfeld's pieces from the 1880's were minstrel songs with slightly syncopated melodies, and with that, Spencer was bound to make hundreds of rounds of any of them. When speaking of this, I mean early on in Spencer's recording days, in the era where he worked regularly with Issler's Orchestra, 1892 to 1896 that is. The solos he made during this time were done under pseudonyms for the most part, but he was still known as the prime coon song singer on phonograph records. With this fame, the composers and publishers took an interest in Spencer, and kept their ears open for a time to hand him an advance copy of a new song. This probably happened with Spencer a few times in the mid-1890's, though it's not well-documented, according to others in the business, it did happen with Dan Quinn and J. W. Myers. Quinn stated in some of his letters to Jim Walsh that publishers handed him songs before they were published to singer before all the others got to it,he claimed to be the first one to sing

This great early Rag song with a very racist cover(typical for 1896...).

I'm not sure whether to believe that Quinn was handed an advance copy of this in 1896, but it's not impossible. I would believe it more if he said that Spencer was the one who got it first. I have seen so many advertisements that mention Spencer's record of "The Bully" as being one of his best records, and the most popular as far as his individual records go. This had to be so, since it was reported that Spencer was making rounds of this tune into early 1898. I don't know who was handed the advance copy first, even if Quinn stated that he was the one who got it first, not everything he said is to be trusted, remember. Other than Quinn's "Bully Song" statement, there wasn't much early music dealing in the era before 1897, though there was probably more than what we are presented in this matter.

It took until the "rag" fad to spread in 1896 for music publishers and composers to take more of a direct interest in recording stars. New publishers such as Joseph Stern took in some of the most popular studio stars under Russell Hunting's obliging with the Universal Phonograph Company. Many of their advertisements are in editions of The Phonoscope, here is their earliest one:

This came from the January 1897 issue of The Phonoscope.

Their ads were often in pieces of music published by Jos. Stern in 1897, of which I have one of these buried in my sheet music collection. They were usually small triangle-shaped things that said simply that the song this is on can be found on records made by the Universal Phonograph Company. That's perfect in illustrating this point of publisher and recording artist, so early on in the era as well. 1897 would be toward the beginning of this idea of uniting the two aspects of the music business, as most people think of this happening in the 1910's and 1920's, but in reality, it began in the late-1890's. The Universal Phonograph Company didn't last to see the end of 1897, but it proved that a publisher could join with a record company to sell music and make records. This quick venture for the Columbia staff got everyone thinking about beginning something else like that, but they needed a better publisher for the job.

Composers still remained friends of many studio stars, such as Barney Fagan and Len Spencer or Quinn and May Irwin. It took until Columbia threw out their old pianist in mid-1897 for this idea to resurface. Fred Hylands was not yet a publisher as we know, but the ideas were formulating. There weren't any reports of music being dealt under-the-table in 1897 and 1898 at Columbia and Edison, but by early late-1898 and early 1899, the staff had begged Hylands enough to begin a publishing firm, and so he did. He was exactly the kind of publisher that Columbia's staff wanted and needed, since he worked there, it all seemed to work perfectly.

No one saw their finish of course.

But that doesn't matter just yet, it was the perfect everything for Columbia. If you really want to talk about some severe under-the-table music dealing, Hylands Spencer and Yeager is the firm to study.

Pretty much everything that Hylands published was given to someone as an advance copy before he published it. This was especially so with anything he wrote(durr...). The instrumental music was given out after publication, but not the vocal pieces. Hylands handed his "You Don't Stop the World from Goin Round" to Len Spencer before he published it, so they could record it first, then sell the music, and he also did this with his "Prize Cake-Walker is Old Uncle Sam", and he gave that one to Dan Quinn of all people(that's kind of strange if you think about it). The ladies that Fred took a liking to eventually were ones who got music before it was published, such as Ada Jones, Sallie Stembler, and some of his wife's friends in the performing business. As the firm began to fade by early 1900, Hylands stopped handing out advance copies, as someone might have told him to end his habit of doing that, or something else, I really don't know, but it seemed that he stopped doing that after the end of 1899. It was around this time that everyone involved saw their finish, or Fred's in this case since he was the one who was going to take the harshest blow after it fell through. After the firm's end in November 1900, the idea of publisher and recording star lost its novelty, and all the old Columbia stars didn't bother to associate themselves with specific publishers or composers any more after that.

The second wave of studio stars adopted some of these ways, as many collectors are aware of the Collins and Harlan friendship with Theodore Morse, which lasted over a decade. Harlan had been part of Hylands' publishing firm, but after about five more years, Harlan was working not only with Collins, but found Theodore Morse a better asset than Hylands, which is many ways was a smart move on Collins and Harlan's part. This 1890's tradition carried on into the 1910's, 20's and even the 1930's in fact, and it seemed to become a much less hidden subject as the decades went on, making it not as sleazy and interesting as it was early on.

*I just want to take a moment to send my love and regards to Tom Brier and his family, as he was recently in an awful car accident and will take many months to recover. We will miss you at Sutter Creek this weekend! Some of the soul of the festival is lost without Brier there.*

Hope you enjoyed this!

No comments:

Post a Comment