Well, it may not be perfectly clear what Fred Hylands' birthday is, but the day that we do have as a guess is February 28th. So in honor of that date(which is probably more likely his wife's birthday), I feel obligated to do a post on him in some way or another.

Like any birthday post, it's hard to determine where to begin with Hylands...Of the three-four years I've done studying him, I've gone from just a single small bio in The Phonoscope to almost a complete picture. There are still so many missing pieces of vital information, which is to be expected, as it's hard to know what the man was really like. Before I get to the bulk of this post, I'd like to share what I know of how Hylands was in terms of character, and just a general outline of him...

It's clear that from a young age that Hylands lived in the typical mentality that being a musician could never be a life-long career. With that mentality, his parents refused to keep him from only pursuing music, despite being pushy about his talents by having him tour around as a child musician. Fred was bright from a young age, and by age 15, he was thrown in business school(likely by his father), and probably learnt a few things about business sense while there. With this foundation, he had confidence in himself in no matter what he went for, and was self-driven. With all of this, moving to Chicago got him his first serious job in the theater business. His success in Chicago and absorbing of new syncopated music got him the confidence to move out of the mid-west that he was used to, and he followed the lead of the other young "rag" pianists and performers(like Ben Harney and Max Hoffmann).

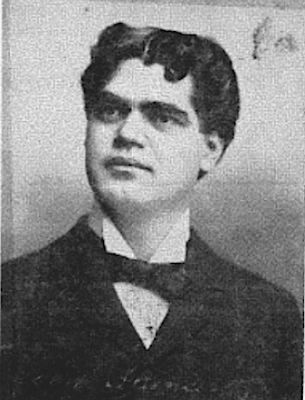

Hylands entered New York with striving confidence and excitement. At this time(1896) he was tall, kind of handsome, and slim, certainly he would have assumed himself "soubrette bait". Once he had a seat at Pastor's theater, being surrounded by younger Rag pianists built up his status in the music community, particularly the budding Rag-Time community. Once Columbia took him in 1897, all bets were off, and most outside gigs of his were too. Once at Columbia, that's where he was practically imprisoned almost every hour of the day, playing one take after another of rounds, and dealing with more singers than he could have than at Pastor's as music director. He soon became weary of this studio work, and it changed him greatly, out of some strange mix of things. We know that he was no longer slim by 1898, for whatever reason, and working at such a sedentary job couldn't have been good for him, with the combination of little sleep(making the switch from actors' hours to the opposite), drinking more often, and just generally losing any sense of self-care, he changed dramatically, and likely seemed not the same person as he was when first getting to New York in 1896. He hated the work at Columbia, as he stated, but of course deep down he loved the theater that he experienced every day at work, particularly from tragedian studs like Len Spencer and the morality lectures from Dan W. Quinn. With the work taking a horrible tole on his body and health, he decided to go into publishing in late-1898, failing at that, but then determined, trying again in early 1899 with his studio idol Len Spencer. His relationship with Spencer seems much more complicated than it was on the surface. Starting in 1897, they saw one another at work almost every day(every day certainly by early 1898), and found that their musicalities had similar chemistry, with that, this is why their records sound a little more perfect than the other recording partners of the brown wax era(like Quinn and Banta). Spencer's vocal style fit with Hylands' weird piano style perfectly, and in a different sort of perfect as Edward Issler's did in the years before that. It didn't help that Spencer's family had roots in the same region as Hylands' birth...

By 1899, the second publishing endeavor was good to go, with Hylands' foundation in business, and Spencer's higher education status in business, it seemed a perfect combination to satisfy Fred's desire to be social with theater freaks. Spencer's beautiful logo sealed the deal on the publishing firm and did just what Fred desired, caught the attention of performers from all around. As his advertisement stated, it was clear that one intention of having this firm was not only to gather up all the recording stars so they could rely on only him for music, but to gain the praises and friendship of many other prominent performers. Among those performers that Hylands, along with his assistant Burt Green attracted to their "33" were Byron Harlan, Ada Jones, Barney Fagan, Fred Hager and J. Fred Helf, and Sallie Stembler. Hylands took a specific liking to each of these performers that Burt and Spencer told him about, since he was not there himself often to greet them when they called. Though the regulars at "33" soon were featured on several sheets of Fred's. A particular interest of Fred's was Sallie Stembler, who was on quite a few of his sheets in the relatively short time he published successfully.

She was already a rising star at the point that she corresponded with Hylands and Spencer. Now nothing definitive can be said about Hylands flirting around with Sallie, but considering the aggressive charm he and his sister Etta had, it wouldn't come as too much of a surprise if he messed around with her a little. His Marie was always gone at night, solely on actors' hours for the most part, and would be getting home from work just shortly before Fred would have to go to work(at Columbia). Without exhibitions at night, Fred had a little more time on his hands he was not intending on wasting...

To add to the weirdness of the Sallie and Hylands thing, Sallie got divorced in 1900 not long after she was being pictured on Hylands' sheet music, and the charge was abuse and infidelity.

Let that sink in for a moment...

When the publishing firm collapsed in the fall of 1900, Hylands held a grudge with all of the fellow managers, and wrote a scathing letter out to them all, expressing his displeasure with them. Even with the unreasonable anger, Hylands still had to continue to face Spencer very often at work(Columbia), and all the other recording stars involved with the publishing endeavor. From this tale, we learn that Hylands was overly ambitious and confident, but unable to keep commitments, as the power he held corrupted him and therefore burnt bridges he built with his closest Columbia friends. Even with the heartbreak of the firm, he continued onward at Columbia, and soon back again into the theater where he really belonged.

(in this show, Hylands played the part of one of many New York character stereotypes, which type, I have yet to find out)

He flirted with the idea of joining a union as early as 1901, as he was surrounded by progressives that expressed their dissatisfaction with their work since the mid-1890's. Issler, Will J. Hardman, Art Young, then later the budding White Rats. After his failed attempt at another publishing firm and a union, he gave in and joined the White Rats. His faulty leadership skills came around again as he rose up in the White Rats, his desire to run around and flirt against the rules ended up being his downfall in 1911-1912. After being a high up leader in the White Rats, being an aggressive leader, his desire to move around and flirt against the rulebook is what condemned him to court in 1911 and got him thrown out of his leadership position of the union's then large network.

His shows outside of the union stuff were sort of successful, as all the big Broadway people seemed to know he was a toxic musical freak to get involved with. They all knew he was an outstanding accompanist, but was full of himself and overly confident with his skills outside of improvising popular songs on piano and violin. His performance skills outside of recording and accompaniment were never really highly praised, but his charm was always what kept him on level with everyone else.

Hylands may not have been the best publisher, or union leader, but his records are really where it's at. When we listen to his records, we get a sense of familiarity out of knowing it's him back there on piano, doing his strange accompaniment that we all know and love. He probably resented working for Columbia for so many years, and was likely ashamed of all the strange and rather horrible things he did while there(as we can well observe that this is the origin of where his health failed him), but it's what physical evidence we have of his footprint in the history of North American music(and recording sound in general). He was not the first studio pianist, nor the first studio pianist to play rag-time, but he brought a style to the recording horn that had never been heard before and hasn't been replicated since then. Like all the other brown wax era studio pianists, he suffered for the sake of making a mark on what we can still hear today as record collectors(though that wasn't really in the mindset of all recording stars at that point in time). He shortened his life by 20 years by working at Columbia, but what he left us is fascinating, as there's no context and stories to accompany the days he sounds different from others, and why he played so strangely sometimes.

We all know about Banta, with his goodness and morality, and his praises from being a tragic story taken from the world too early, but in reality, Hylands was similar in a lot of ways.

Tragic indeed, the story of a fantastic musician intended to be a businessman who strays away from this to become a theater manager, then at the height of success is pulled out to the lowest kind of work for a musician in the 1890's, the recording studio. The studio changes him from a funny country jay to a drugged, greedy, bitter young city rat. he tries to escape this life after the era of piano accompaniment fades to join back in theater, and rises high up once more in the advocation for his fellow performers, but his fatal attribute leads to his downfall. This attribute is adventure and habit. The downfall is deepened at the death of his father and he ultimately finds himself dead in another nation in the middle of a reviving tour.

what a story!

Just as tradition, here are a few records with Hylands accompaniment. There are so many out there, I cannot even begin to choose some, here are a few good ones anyway:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3cXPziKyIEA&t=94s

Hope you enjoyed this!