Banjoists Ruby Brooks(1861-1906) was on the same level of banjo skill as Vess Ossman, but in some ways, Brooks presented a banjo style that was eccentric and primitive in ways that others weren't.

Brooks made enough records for record scholars to get hints as to what the more folksy banjo styles sounded like in the early years of the rag-time era. Keep in mind that Charles Asbury's style is as folksy as it gets, and the best it gets, as he was a black man born in Florida at the end of slavery days and learned to play the banjo from the best black performers of the later minstrel era. There is no comparison between the white recorded banjoists and black banjoists of the time, as the authenticity and dynamics of Asbury wins out the recorded white banjoists.

Ossman and Brooks were equivalent adversaries, doing exactly the same repertoire at the same time, and playing at the same places. One familiar accompanist tied them together, despite their powerful senses of pride. In 1893, in a Lyceum Catalog, there lies this advertisement:

Banta!

There he is with Master Ossman. It's very likely that Ossman shoved Banta into the recording studio, and got him that regular job there for the next ten years of his life. Ossman and Banta were a package it seems, at least for a few years, by 1896 splitting up as an official duo to allow more studio time for Banta. But luckily for Banta, we know Ossman was notoriously difficult, so splitting with old Vess must have been good for Banta's soul. What has this to do with Ruby Brooks? Well, it turns out than Banta showed an interest in Brooks toward the end of the 1890's. With Ossman being chained to Columbia's contract for a little while in 1898 and early 1899, this allowed for Edison to take in the other famous "banjo king" Ruby Brooks. That's exactly what they did, and the end result from that is a handful of outstanding records that surpass many of Ossman's records with Banta from a few years before. Brooks brought a style to recording that was very unlike Ossman's. It was much smoother in terms of syncopation, and even though it was sometimes out of whack and stumped Banta, it's charming in a way that Ossman's style wasn't always. Ossman's style perfectly exhibits his control-freak nature, as he was always in tune, and the rhythm was precise down to the quickest 32nd notes. Ossman when he was interviewed often stressed how important it was for the banjo to be in tune and for the rhythm played to be precise throughout. This is why we don't get any extra or dropped measures in Ossman's playing.

Unlike Ossman, with Brooks we get a very interesting mix of folk aspects that Ossman cast aside in the logic of his playing.

Here's an outstanding example of Brooks' playing:

http://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/search.php?queryType=@attr+1=1020&num=1&start=1&query=cylinder14584

Unlike Ossman, with Brooks we get a very interesting mix of folk aspects that Ossman cast aside in the logic of his playing.

Here's an outstanding example of Brooks' playing:

http://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/search.php?queryType=@attr+1=1020&num=1&start=1&query=cylinder14584

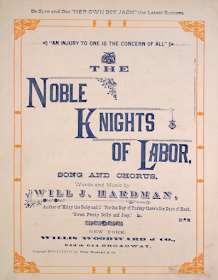

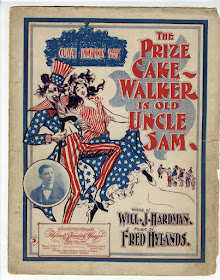

Now keep in mind that the accompanist here is Banta. Really listen to how ragged and smooth those last two strains are! Just a few years before Banta was working only with Ossman outside of the studio. Now, by 1899-1900 Banta had built a relationship with Brooks that provided some curious benefits. Brooks and his long-time partner Harry Denton had set up a publishing firm in the mid-1890's, and by the end of the decade had proved a popular publisher for recording stars and popular performers. With Brooks officially in the recording business, it made more sense to publish some fellow studio stars' work. That's just what he did. In 1899-1902, Brooks and Denton published some of Banta's most popular music, including Banta's "Ragged William"

(from Bill Edwards' website)

Brooks and Denton also published Banta's later work "Halimar", which is an oriental dance(don't have a decent picture of the cover though...). With Brooks' founded interest in Banta, it's likely that Brooks published the last bunch of Banta's work. Banta was only doing his job by accompanying Brooks at Edison, but it's clear that Brooks took a greater interest in the former Ossman accompanist. Their records prove a partnership that fits together better than ever. Banta's syncopation was just as smooth and graceful as Brooks', as can well be heard in the recording of "Hunky Dory Cake-Walk" above. This particular record is the best of the best in terms of Brooks' records in fact. The others that provide good examples are nice, but can't compare to the "Hunky Dory" take.

Here's another good one from around the same time:

https://archive.org/details/RubyBrooks

It's an awful shame the piano accompaniment is so obscured by the crappy transfer. That's okay though, we get to hear Brooks' unequalled and unique skill loud and clear. What makes Brooks so different from Ossman is that Brooks had no formal training to play the banjo. Like singer Frank C. Stanley, Brooks learned how to play the banjo completely on his own and from hearing the old black banjoists around him. This is what makes Brooks style more authentic and attractive on records. His entirely itinerant style comes through on each of his records, and makes them all the more unique. This is what tied together Banta and Brooks, and what makes their records just that extra amount of special that Ossman's just aren't. Banta, as far as we know, was self-taught at the root of his style, and with perfect pitch that would provide reason for little musical training beyond basic theory studies.

Banta, even though he had experience with Ossman and provided for some very sleek examples of banjo rag-time(accompanying Ossman), added something special to records he made with Brooks.

Just to further illustrate this, here are a few more examples:

https://archive.org/details/CoonSongMedleyByRubyBrooks1897-1899

This one is almost just as good as the "Hunky Dory" take.

https://ia802609.us.archive.org/30/items/CollectedWorksOfRubyBrooks/HappyDaysInDixie1905_64kb.mp3

https://ia802609.us.archive.org/30/items/CollectedWorksOfRubyBrooks/StarsAndStripesForeverMarch1902_64kb.mp3

That's as far as the Brooks transfers go online. There's not that much out there to hear unfortunately, but all that stuff gives us a pretty good picture of his style, and that he lives up to his itinerant roots. Considering Ossman's straight and set ways of banjo playing, he must have found the gift that Brooks had to be lesser, but working with Banta would have granted some respect in Ossman to the self-taught banjoist. If you think about it, Brooks isn't playing too differently from those outstanding unknown banjo player:

http://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/search.php?queryType=@attr+1=1020&num=1&start=1&query=cylinder12991

I wish there was some way to know who this amazingly folksy and rhythmically perfect banjoist is. Much of how the unknown banjoist plays that tune is similar to how Brooks played it on an Edison record in 1899 or so.

So in considering all of that, we ought to build up an appreciation for Brooks' records, as before doing some more critical analysis of his records, I didn't find him all that interesting. Before digging in, I assumed that those handful of Climax records Brooks made in 1901 were the best representations of his playing style, but it turns out that was not true at all. These Climax records were questionable in quality, as the only thing you can hear at all is the piano(which is great for studying the pianist, Hylands!), and the banjo is basically not present in the music whatsoever. These records made me believe that Brooks wasn't the best banjoist, and therefore skim through them without interest. After digging into Brooks' story, it seemed more tantalizing and interesting than Ossman's, in terms of stylistic features. Other than all this, the records where this balancing issue was in place were very well made, as those are the examples listed above with Banta piano accompaniment. I wouldn't be able to tell why those Climax records are so out of whack, but every one of them sounds like the way I described. But setting those records aside, Brooks was a great banjoist with quite an interesting style that ought to be studied more often. We often look to Ossman's easy to find and listen to style, but when we step out of the usual Ossman and Van Eps records we find banjoists who were entirely unique, but were unfortunately thrown out of recording rather quick due to Ossman's essential monopoly on banjo records before 1910. There's also Fred Bacon to listen to. Bacon was an absolutely outstanding banjoist, who played very similar to the great Tommy Glynn:

This tintype of Glynn is still floating around out there in the depths of Ebay for nearly $2,000. Hopefully someone can negotiate a reasonable price for this beautiful little thing.

Glynn was considered the best of these banjoists, and his untimely death at only 25 further created a sort of cult for the former competitors of Glynn's. These former competitors played Glynn's pieces all over, including Ossman, who recorded several of Glynn's pieces for all labels he worked for. This is where we get records like Fred Bacon's 1912 recording of Glynn's "West Lawn Polka". Brooks didn't record any of Glynn's pieces, but it's clear that all those fellow banjoists like Brooks and Ossman very much enjoyed sharing Banta's accompaniments. Considering Banta's status as a popular instrumental accompanist, without much doubt he must have accompanied every one of these famous banjoists, including the obscure Berliner duo Cullen and Collins.

Now then!

I just joined Ancestry and have been stuck learning an overwhelming amount of new information about a variety of recording stars and performers. Before I decide who to pair together in terms of who to write about next, here's a portrait of Victor Emerson's daughter Edna(born 1899) around the early 1920's:

What!

She's absolutely gorgeous! It's curious so see such a beautiful face to come from a notoriously hated man of the Columbia studio. She looks a bit like her uncle Georgie, with those intense and shadowy eyes, and the slightly poked in cheeks of her father and uncle Georgie.

That's all I'll leave here now before I begin with all the new information in the next posts.

(from Bill Edwards' website)

Brooks and Denton also published Banta's later work "Halimar", which is an oriental dance(don't have a decent picture of the cover though...). With Brooks' founded interest in Banta, it's likely that Brooks published the last bunch of Banta's work. Banta was only doing his job by accompanying Brooks at Edison, but it's clear that Brooks took a greater interest in the former Ossman accompanist. Their records prove a partnership that fits together better than ever. Banta's syncopation was just as smooth and graceful as Brooks', as can well be heard in the recording of "Hunky Dory Cake-Walk" above. This particular record is the best of the best in terms of Brooks' records in fact. The others that provide good examples are nice, but can't compare to the "Hunky Dory" take.

Here's another good one from around the same time:

https://archive.org/details/RubyBrooks

It's an awful shame the piano accompaniment is so obscured by the crappy transfer. That's okay though, we get to hear Brooks' unequalled and unique skill loud and clear. What makes Brooks so different from Ossman is that Brooks had no formal training to play the banjo. Like singer Frank C. Stanley, Brooks learned how to play the banjo completely on his own and from hearing the old black banjoists around him. This is what makes Brooks style more authentic and attractive on records. His entirely itinerant style comes through on each of his records, and makes them all the more unique. This is what tied together Banta and Brooks, and what makes their records just that extra amount of special that Ossman's just aren't. Banta, as far as we know, was self-taught at the root of his style, and with perfect pitch that would provide reason for little musical training beyond basic theory studies.

Banta, even though he had experience with Ossman and provided for some very sleek examples of banjo rag-time(accompanying Ossman), added something special to records he made with Brooks.

Just to further illustrate this, here are a few more examples:

https://archive.org/details/CoonSongMedleyByRubyBrooks1897-1899

This one is almost just as good as the "Hunky Dory" take.

https://ia802609.us.archive.org/30/items/CollectedWorksOfRubyBrooks/HappyDaysInDixie1905_64kb.mp3

https://ia802609.us.archive.org/30/items/CollectedWorksOfRubyBrooks/StarsAndStripesForeverMarch1902_64kb.mp3

That's as far as the Brooks transfers go online. There's not that much out there to hear unfortunately, but all that stuff gives us a pretty good picture of his style, and that he lives up to his itinerant roots. Considering Ossman's straight and set ways of banjo playing, he must have found the gift that Brooks had to be lesser, but working with Banta would have granted some respect in Ossman to the self-taught banjoist. If you think about it, Brooks isn't playing too differently from those outstanding unknown banjo player:

http://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/search.php?queryType=@attr+1=1020&num=1&start=1&query=cylinder12991

I wish there was some way to know who this amazingly folksy and rhythmically perfect banjoist is. Much of how the unknown banjoist plays that tune is similar to how Brooks played it on an Edison record in 1899 or so.

So in considering all of that, we ought to build up an appreciation for Brooks' records, as before doing some more critical analysis of his records, I didn't find him all that interesting. Before digging in, I assumed that those handful of Climax records Brooks made in 1901 were the best representations of his playing style, but it turns out that was not true at all. These Climax records were questionable in quality, as the only thing you can hear at all is the piano(which is great for studying the pianist, Hylands!), and the banjo is basically not present in the music whatsoever. These records made me believe that Brooks wasn't the best banjoist, and therefore skim through them without interest. After digging into Brooks' story, it seemed more tantalizing and interesting than Ossman's, in terms of stylistic features. Other than all this, the records where this balancing issue was in place were very well made, as those are the examples listed above with Banta piano accompaniment. I wouldn't be able to tell why those Climax records are so out of whack, but every one of them sounds like the way I described. But setting those records aside, Brooks was a great banjoist with quite an interesting style that ought to be studied more often. We often look to Ossman's easy to find and listen to style, but when we step out of the usual Ossman and Van Eps records we find banjoists who were entirely unique, but were unfortunately thrown out of recording rather quick due to Ossman's essential monopoly on banjo records before 1910. There's also Fred Bacon to listen to. Bacon was an absolutely outstanding banjoist, who played very similar to the great Tommy Glynn:

This tintype of Glynn is still floating around out there in the depths of Ebay for nearly $2,000. Hopefully someone can negotiate a reasonable price for this beautiful little thing.

Glynn was considered the best of these banjoists, and his untimely death at only 25 further created a sort of cult for the former competitors of Glynn's. These former competitors played Glynn's pieces all over, including Ossman, who recorded several of Glynn's pieces for all labels he worked for. This is where we get records like Fred Bacon's 1912 recording of Glynn's "West Lawn Polka". Brooks didn't record any of Glynn's pieces, but it's clear that all those fellow banjoists like Brooks and Ossman very much enjoyed sharing Banta's accompaniments. Considering Banta's status as a popular instrumental accompanist, without much doubt he must have accompanied every one of these famous banjoists, including the obscure Berliner duo Cullen and Collins.

Now then!

I just joined Ancestry and have been stuck learning an overwhelming amount of new information about a variety of recording stars and performers. Before I decide who to pair together in terms of who to write about next, here's a portrait of Victor Emerson's daughter Edna(born 1899) around the early 1920's:

What!

She's absolutely gorgeous! It's curious so see such a beautiful face to come from a notoriously hated man of the Columbia studio. She looks a bit like her uncle Georgie, with those intense and shadowy eyes, and the slightly poked in cheeks of her father and uncle Georgie.

That's all I'll leave here now before I begin with all the new information in the next posts.

Hope you enjoyed this!